Five Future Comic Classics: Part IV

Exhibit IV: Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986); DC Comics, Inc.:

“Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.”

~ Friedrich Nietzsche

It’s impossible to say which of today’s favorite comics will be extant decades from now and which ones will be relegated to the dung heaps of history… Yet it is precisely this daunting task that we have taken upon ourselves in this fourth installment of tomorrow’s classics. In our last review, we looked at a Marvel classic. This week we go to the Distinguished Competition—DC. Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986) continues to be a bestseller (32 years after it’s debut), and if current trends are any indication, it’s quite likely that the trade paperback, already in its third edition, will be around for many years more.

When the four-issue series arrived on the scene in the mid-eighties, its impact on Comicdom was paradigm changing. Batman’s Pollyanna image became irrevocably lost; gone was Adam West’s campy portrayal of Batman, the smiling happy-go-lucky face of yore, and the biffs and bams that so characterized the pre-1986 Batman. In its place was something darker—and far more profound. Readers embarked on a Conrad-like odyssey penetrating “…into the heart of darkness” as Miller introduced readers to a dystopic Gotham whose “heroes” were as psychologically damaged as the villains they pursued.

Frank Miller first achieved prominence with his work on Daredevil. The combination of good writing and exceptional artwork, transformed that lackluster series–from a bi-monthly book with a dwindling readership–into a monthly book worth reading. Miller became one of those rarified few whose storytelling was equal to his penciling. He has since gone on to produce some remarkable stories, viz. Ronin, Sin City and 300, but unquestionably, his magnum opus remains Batman: The Dark Knight Returns.

The story features an aged Batman who comes out of retirement after a ten-year hiatus. Miller aptly portrays a middle-aged man, struggling and coping with the aches and pains that accompany age and a body that has experienced decades of pounding. To compete with the times, the aged crime fighter must now rely on his wits, his wealth, and the assorted tools of the trade. Readers are presented with a Batman who now sports a bullet proof vest, employs gas ampules, uses disguises, guns, an exoskeleton and a suped-up Batmobile that has been converted into a veritable tank. In this universe, the stakes are higher: the villains and heroes play for keeps.

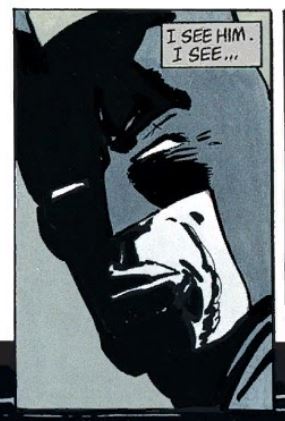

Bruce must find out if Harvey has changed—indeed, his own mental state hinges on it. In the end, Two-Face’s rehabilitation and plastic surgery (which Wayne personally paid for) have proven as ineffective and bogus as Batman’s retirement; proving the proverb, “one beetle recognizes another,” he sees him and replies, ” I see a reflection.” (Hence the expression, “bat-shit crazy”.)

Miller begins the series by delving into Batman’s raison d’etre. The Batman has been absent from Gotham City and is presumed dead. Retirement suits the 55-year-old billionaire who indulges in the appetites of the 1% and turns a blind eye to the increasing violence around him. When a large bat crashes through his window, however, the traumatic events that took placed in Crime Alley are reawakened. Wayne experiences a relapse, and like a junkie, returns once more to his cape and cowl.

Along the way a teenage girl named Carrie Kelly joins him. Tech savvy and resourceful, she assumes the identity of the late “Boy Wonder.” In the caped crusader’s struggle against the Mutants, “a kind of evil we never dreamed of…” Kelly’s assistance proves pivotal in Batman’s struggle with the beastly villains.

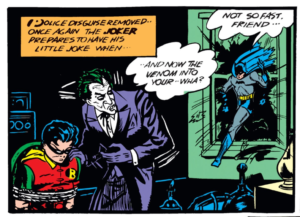

Batman #1 (1940): From the onset, the Joker knew that Robin was Batman’s greatest liability. And in “A Death in the Family (1988)” he would finally kill him.

Frank Miller envisions a liberal Gotham City, which coddles its criminals and criminalizes its victims. Batman is pursued and hunted by the city’s law enforcement as a base vigilante, whose heavy-handed techniques are condemned. As Gotham’s mayor fiddles and the city burns, the Joker, that quintessential mastermind of crime, patiently bides his time in a psychiatric ward, watching and waiting. Joker has been given the aspect of one who is truly psychotic; a maniacal mass murderer that makes today’s terrorists look like pikers. This version was more in line with the Joker as he originally appeared in Batman #1. In the following years (principally, the 1950s) the Joker had been watered down to the point where he had become something (pardon the pun!) of a joke. Miller not only builds on the Joker revival that was begun by Dennis O’Neil in the ‘70’s, but also restored Joker to his rightful place as Batman’s arch-nemesis and most dangerous foeman. Miller’s Joker becomes the template which future writers would follow and which would later form the basis of the character’s personality in the Batman movie franchise.

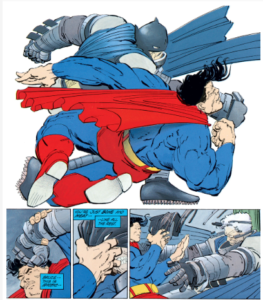

As Batman ties up loose ends and past villains, the series concludes with the greatest detective locked in heated combat with the de facto demigod, Superman. The Man of Steel—that paragon of “truth, justice and the American way”—is portrayed as a Reagan apparatchik, sent to rein in the Batman—who has become a loose cannon and embarrassment to the federal government. The battle that ensues is epic. Through Miller’s distinctive artwork, the reader vicariously feels every Spillane-like body-crunching blow: replete with shattering bones and the splatter of blood. The story’s denouement effectively underscores the rift in ideals and methods between the two crime fighters—something that may have been hinted at in the past but which was never quite articulated.

The Dark Knight remains one of the most iconic books to this day and has no analogs. It’s largely responsible for ushering in the Modern Age of Comic Books—where realism and dark themes became the norm. Frank Miller effectively restructured the Batman series and cemented Batman’s primacy in popular culture. In the process he transformed the one-dimensional character of pulp into the complex (if not the slightly disturbed) hero we see today. If the Watchmen is, as the BBC suggests, “The moment (when) comic books grew up,” then the Dark Knight is the moment when the superhero comic became literature.